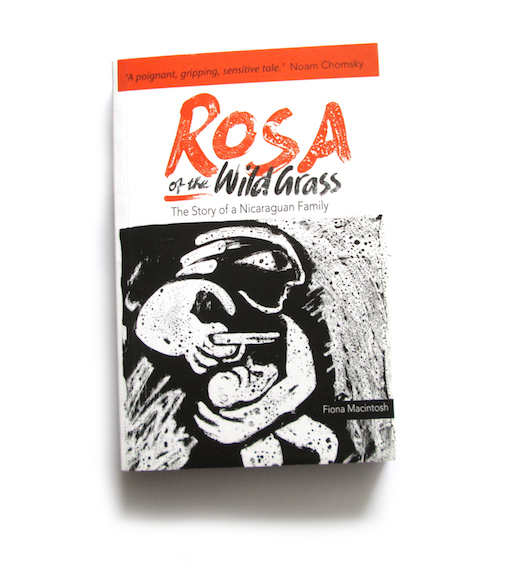

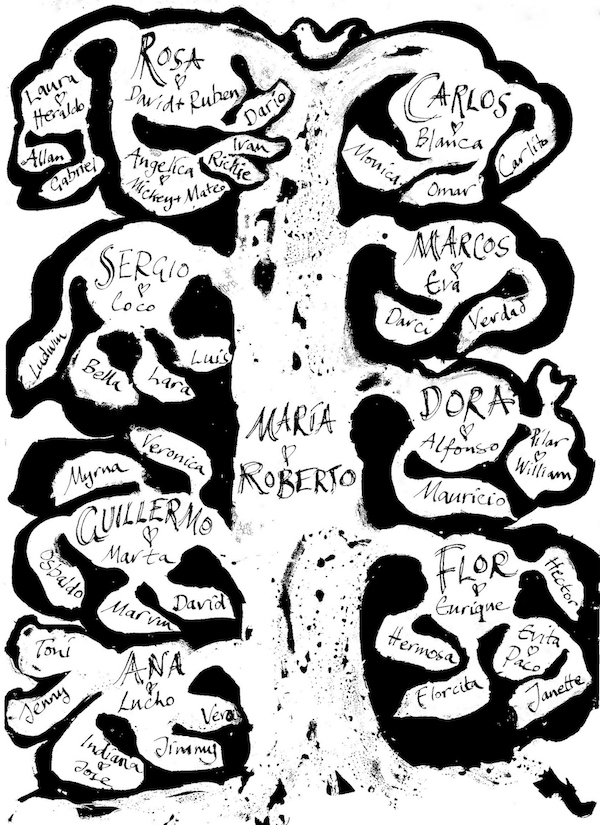

Rosa Family Tree

1 Between you and me

It is 1987, some eight years since the bloody insurrection and overthrow of the Somoza dictatorship. The government, confirmed by elections in 1984, is formed by the FSLN, the Sandinistas. Rosa is now thirty-six, and María, her mother, in her late fifties.

Rosa

Did you hear Marcos banging on the door last night? What a racket: 'Madre mía, let me in! Son of a bitch, this is my bloody house!'

Bring your coffee; we can talk under the tree. His mind gets working when he's drunk, especially when I'm home. He's always been jealous of me. He says I've no right to be interfering; he's the one in charge. He knows I've told mum to sell the smallholding outside town and enjoy the money. She should; mum has worked all her life and should be taking it easy. Even now she won't take a weekend off. For her, life is work. If she sold now it would avoid a lot of bother later on. The trouble is dad told Marcos he was to look after the household affairs once he passed away, and now Marcos is saying this isn't the time to sell, that there isn't the market and mum should go on selling the oranges and mandarins. He's right in that there's not much demand for land since the agrarian reform. But I know what my brother is really up to: he's banking on inheriting the land after mum dies.

His drinking is out of hand. I don't like it. I only ever saw dad drunk once or twice. There was none of this shouting, waking the ghosts. If ever dad had a drink on him he'd quietly ask mum to hang up the hammock and he'd take a nap; that was all. The guaro was brewed only for men to relax after a hard day's work, to sit out and have a chat.

1

When passing Los Cocos on the bus up here, the woman sitting beside me told me she'd gone to see the herbalist in Los Cocos about her boy. She said he was sleeping rough, out of his mind on drink, but after she gave him the herbal remedy it was as if he became brand new. Now Marcos could do with a dose of that.

'Madre mía, let me in!'

No, you don't want near him when he's on one of his binges. He'll be gone for days after he's brought in the harvest. He's in a cooperative now. He's never left La Concha.

* * *

It was us girls who left to go to the city to earn some cash. I left when I was 13. We weren't that poor but money was always tight. That was 1964, when I finished at the local primary school in La Concha. I'd attended with my five brothers and sisters. The older ones had already left when I started.

2

I did pretty well at school and when I was 12 the school held a small assembly. In those days they didn't have this Band of Excellence for the best student but the school director told me, 'Rosa, you've always been very studious and had top marks. You must go on with your schooling; there's a bright future ahead of you.' She said I should tell my mum and dad to register me for high school.

I felt so proud telling dad, 'The director said I'll have a bright future if I go on to high school. She said there'd be no cost other than the uniform and school materials.'

Dad said, 'Well, that's good to hear, but you've finished school now.' He wouldn't listen. 'No Rosa. It's the boys who need an education. They're going to have the responsibilities of wife and family. When you find a good man, he'll keep you.'

I didn't understand so went to mum. 'Dad says I can't go on to high school. What am I supposed to do?'

'Now there's plenty to get on with: the coffee picking and you can go and help plant the corn.'

'But I don't want this. I'm going to find some other work.'

In the end I was stuck at home doing all the household chores.

My friends all knew what had happened. Terri, who I knew from church, kept saying to me, 'Maybe your dad will change his mind.'

'If he hasn't in a year, he's not going to now. You know what he's like. I'll look for a job.'

I thought that would at least be better than washing and cooking at home; I'd be earning. It was normal for girls like me to go to the city for work. You'd hear that kind of thing on the bus. 'Juanita, she's left, got a cleaning job in Managua, and her sister, she's with a big coffee family.'

3

So I asked Terri to keep an ear out. 'Whatever you find tell me; any job... like cleaning.' She was a year older than me and I saw her as very grown up. She went to Managua a lot to visit her relatives.

A week later she came to find me. 'Listen, my cousin needs someone to be with her. I think it won't be more than keeping her company and the flat is really small.' Her cousin had just got married but the husband was never home so the young bride was lonely and her mum felt she needed someone to be with her.

'Ideal. I'll go.'

In my head I was already on my way when I told mum. I asked Terri to come too, to put mum's mind to rest. But she said a lot more. She said, 'Rosa wants to go because she wants to study.'

'But how do you know they'll let Rosa out to go to school?'

'I'll find out,' I said.

In the end mum gave in. 'Well, I'll need to know who these people are.'

Dad was upset too, but that next Sunday I was on the bus to Managua with my bag. Mum came with me.

The wife's name was Pata. She was only a few years older than me and Terri was right, there was little to do other than wash the dishes and clothes. The only thing was, back home we didn't have a tiled floor so mopping the floor was all new to me. I broke a crystal vase and a couple of plates and Pata's mum gave me a terrible time for that. I began wondering if I'd made a big mistake and should go home. But when I was paid for the first time, I felt 30 córdobas was a ton of money and I stayed on.

But 30 córdobas wasn't enough to pay for evening classes and after eight months had rolled by I heard of another position. A maid I often met at the corner shop told me a woman in her block was looking for a maid from out of town. 'Why not try? Doña Nuevia wants a live-in maid, someone reliable.' When she said the pay was 60 córdobas, I said, 'that's me.'

4

Pata was now pregnant and her mum wanted an older maid for her, so all round my leaving was fine.

Doña Nuevia obviously wanted more for her 60 córdobas than just cleaning. She wanted me babysitting all the time. At least I was now saving and when I had enough to enrol in school I asked Doña Nuevia for time off, but she said, 'My dear, that's exactly why I need you, to allow me to go to night classes, and the other evenings I need you here for when I have visitors.'

It took two years before I found a day job with Angela and her husband in Managua. And my Aunty Tina, one of my dad's sisters, offered to let me move in with her and her daughter. For me Tina was like a second mum; she was a real support.

At last I was going to the Pan Americana School in the Monseñor Lezcano barrio. I went there for two years and passed all my exams.

Then Tina suggested I go to technical college. University wasn't on the cards but I wanted to learn a skill so I applied to a college near Cuidad Jardín to learn typing and bookkeeping. The classes ran from six to eight in the evenings. I had this voice in my head saying, 'Stick with it, keep going; in the end you'll have a proper job and proper money,' but at the same time I knew the money I was spending on college was needed back home.

Once I qualified, I went looking for secretarial or bookkeeping jobs. I looked everywhere, even in the Eastern Market, but it was 1970 so businesses were shutting down and no investment was happening in the country. All that effort ended up with me being no better off. I was stuck in my maid's job.

* * *

5

It was then I met David. He used to come by the house where I was working selling bread every day. He asked me where I was from and when I told him La Concha he said he was from there too. He knew of my dad and mum and also Aunty Tina. And soon as he knew I was sleeping over at Tina's, he began dropping in to see me there. I was only 18, way too young and all wrapped up in myself. All I knew about a man and a woman was what mum had said, which was, 'Give one good reason why a man should hold a woman's hand.' Truly. I never saw mum and dad openly show affection. And they didn't know about David. No, in those days no one talked about contraceptives, but they weren't available anyway. Birth control wasn't something anybody talked about, much less sex. When I got pregnant I kept it private, secret, and I felt terrible.

When slowly the bump began to appear, Tina asked me directly and I just broke down in tears and told her. She was really shocked. She thought I'd have had more sense. She was kind though. I asked her if she would tell mum for me, ha, and of course when she told them, mum got upset and dad was furious with Tina for allowing this to happen under her roof.

I felt so bad I asked the woman I worked for, Angela, if I could stay at their place. And she said yes. She made me feel at home. I'll always be grateful to her. She's a nurse and that was a real blessing; she understood what I was going through.

For the duration of my pregnancy I hardly ever went out, fearing I'd see Tina, and I hardly saw David. He was too macho. Whenever I'd gone anywhere with him he wouldn't let me wear makeup, wanting me to look like a nun in a long skirt, and he'd introduce me to his friends as his woman.

I'd told him 'No, I'm not your woman. I'm Rosa and I'm used to working, going out, looking smart and I've got friends who want to see me, and I want to see them.' He didn't even like me seeing my pals from college. I couldn't take how he tried to control me and after six months my love for him was over, way before Laura was born we'd parted company. I was 19 when I had Laura.

6

Angela and her husband were very kind. Angela kept sending me for prenatal check-ups at the hospital. I gave birth there and only Angela was with me. Laura's birth changed everything. David, though, wasn't willing to accept our separation. He came to Angela's to try and persuade me to go back. I told him, 'It was hard enough giving birth. Please, I don't need any more grief.' He'd just wouldn't take no for an answer. 'Come on, we can make a go of this,' he'd insist.

'How can we if I'm not the person you want me to be? I am Rosa, and I know it won't work. Laura and I are going to be fine; so don't worry.' He kept turning up on the door step until at last I heard he had another girlfriend. What a relief when he stopped coming.

* * *

All this time I hadn't been home. I knew mum was worried and she must have talked Dad around because Tina came to tell me I should go home with Laura. But when I did, dad gave me such a telling off, letting me know exactly what he thought, saying I should be in a proper relationship and married. It was my brother Sergio who came to my rescue. He said David was a bully and a drunk, which wasn't true. David had no bad habits like drinking, but I wasn't going to argue.

Despite Mum and dad being annoyed, they didn't reject me and I saw mum loved Laura. They accepted her into the home. Once Laura was a toddler she went to stay with them. Mum saw to it that she went to school, gave her the security she needed, and pushed her in her studies. I simply wasn't in a position to do that. It was for the best. It's only to be expected she grew up to feel close to her granny, closer maybe than to me, and yes, that has made me sad. I had no choice but to work and make sure Laura had what she needed.

7

Laura has always been top of her class. She's 16 now. I can see how she holds her own. She's grown into a bright, mature young woman. I could depend on mum. My sister Ana wouldn't have bothered herself. Ana doesn't see the importance of education. She still lives at home with mum and her family. What really got my goat was how she'd use Laura to do her washing and at the same time pretend she bought Laura her clothes. When I found out I told Laura, 'It's only right you respect your Auntie Ana. But Laura, I'm your mother and I'm the one who pays for everything you need. If ever I didn't, you'd be the first to know.' I made sure I said this in Ana's hearing and then I told Ana that Laura wasn't her maid. I'll never forget that and I doubt she has.

It was Mum who wanted the best for Laura and that was to learn. Mum treasured education. I'd often heard her say so. I remember when I was small, it was at the end of mum's class and dad came in and for some reason I asked him if he could read and he said he wished he could and, there and then, mum sat down beside him with her books and started to teach him. Why Dad didn't send me to high school was because money was always tight. They had to sacrifice a lot to see Carlos and Sergio go to college. And Dora too; she trained to be a seamstress.

Dora paid them back soon as she could, after she set up the sewing co-operative. That was a real success for her. She set it up with other women in La Concha. That was soon after the Sandinistas came into power in 1979.

Too bad Dora hasn't the same get-up-and-go regarding her husband, Alfonso. He thinks I give Dora ideas but he's got no worries there. Before she married I tried telling her, but she insisted, 'If I don't marry now, when will I?'

'It not when you marry, it's who you marry.'

He's another drunk, like Marcos.

8

She had a choice and she must have known what she was letting herself in for. Her marriage hadn't been arranged. In my parent's time it would have been. Yes, my grandparents arranged for mum and dad to marry. That was the custom then. I suppose my grandparents must have thought they'd make a good couple, saying, 'María makes fine tortillas, and nothing is too much of a chore for her', and Roberto being hard-working and honest. Then Mum was told to see the priest, and two weeks later she and dad walked down the aisle. That's what mum told me. And look, they were well suited. They must have been; they stayed married for 50 years.

In those days you had to respect your parents. If you didn't, you could be cut off. My Sunday school teacher, Lucía, a tall elegant lady, looked almost like the Virgin Mary herself. The problem was her dad; he was too strict with her. He said he was waiting for the right man for her and that's why she was still single at 29. Then one day a farmhand turned up to pick coffee. I heard people in church saying, 'Lucía's talking to that peasant. He must have sprinkled that magic potion Sontin by her window.' Folk thought he'd put a spell on her. But soon as her dad got wind of this he sent the man packing.

No one imagined Lucía would run away. This was a mortal sin for the family. For months no one saw her parents. They kept behind closed doors. And no one saw Lucía, not for another year until after she had her baby.

Her father gave her a smallholding outside La Concha where she still lives with her man. He gave the land to save face, but she was cut off and never seen in church again. She only appeared in town to sell tortillas. All that happened when I was a small girl.